The End of Long-Lived Secrets: How Workload Identity Federation is a Security Superpower

Table of Contents #

- Introduction

- The Problem with Long-Lived Secrets

- Workload Identity Federation: A Modern Solution

- Token Exchange & Verification - Under the Hood

- Security Considerations

- Conclusion

Introduction #

As a DevOps Engineer, I’m tasked with ensuring secure and efficient communication between our various cloud and SaaS services. One of the most persistent challenges I encounter is managing long-lived secrets like API keys and service account credentials. These secrets are often left unrotated, creating security vulnerabilities and operational burdens.

I’ve recently been exploring Workload Identity Federation (WIF) as a solution to this problem. WIF allows workloads to authenticate with cloud services using short-lived tokens, eliminating the need for long-lived secrets, turning identity into a security superpower rather than a liability. In this post, I’ll cover how WIF works, its benefits, and how it can help organizations improve their security posture while reducing operational overhead.

In future posts, I’ll dive deeper into specific scenarios showing how I’ve used WIF at work to eliminate long-lived secrets and improve our security practices.

The Problem with Long-Lived Secrets #

Long-lived secrets, such as API keys and service account credentials, have been the backbone of service-to-service authentication for years. However, they come with some significant drawbacks:

Risk of Leakage: Long-lived secrets can be leaked through various means, such as code repositories, misconfigured permissions, or accidental log output. Once compromised, these secrets can be used by attackers to gain unauthorized access to services.

Credential Rotation: Regularly rotating long-lived secrets is crucial for maintaining security, but it can be a cumbersome process. If not done correctly, it can lead to expired credentials, causing service disruptions and outages. Many organizations struggle with this, leading to a reliance on extremely long-lived secrets that are never rotated.

Operational Overhead: Managing long-lived secrets requires additional operational overhead, including tracking when secrets were last rotated, ensuring all services are updated with new credentials, and monitoring for potential leaks.

Workload Identity Federation: A Modern Solution #

WIF offers a modern solution to the problems associated with long-lived secrets. By leveraging the OpenID Connect (OIDC) standard, WIF allows workloads to authenticate with cloud services without the need for static credentials. Here’s a high-level overview of how it works:

Establishing Trust: A human administrator performs a one-time setup step to establish trust between the two systems that need to communicate. This is done by configuring the Identity Provider (IDP) and the Relying Party (RP) to recognize each other. The IDP is responsible for issuing identity tokens, while the RP is the service that the workload wants to access.

IDP issues an ID Token: When a workload needs to authenticate to the RP, it requests an ID token from its own IDP. This token contains information about the workload and is signed by the IDP’s private key. Sometimes, this ID token is pre-fetched and made available to the workload via an environment variable or a file.

ID Token Exchange: The workload then exchanges this ID token with the RP for a short-lived access token. During the exchange, the RP verifies the ID token’s signature and claims, ensuring that the workload is authorized to access the service.

Workload Access: Once the workload has exchanged the ID token for an access token, it can use this token to make authenticated requests to the RP. The access token is typically short-lived, reducing the risk of long-term exposure. In the case of systems like GitHub Actions, the access token is typically valid for a limited time and is immediately revoked after the workflow completes.

Example Scenario #

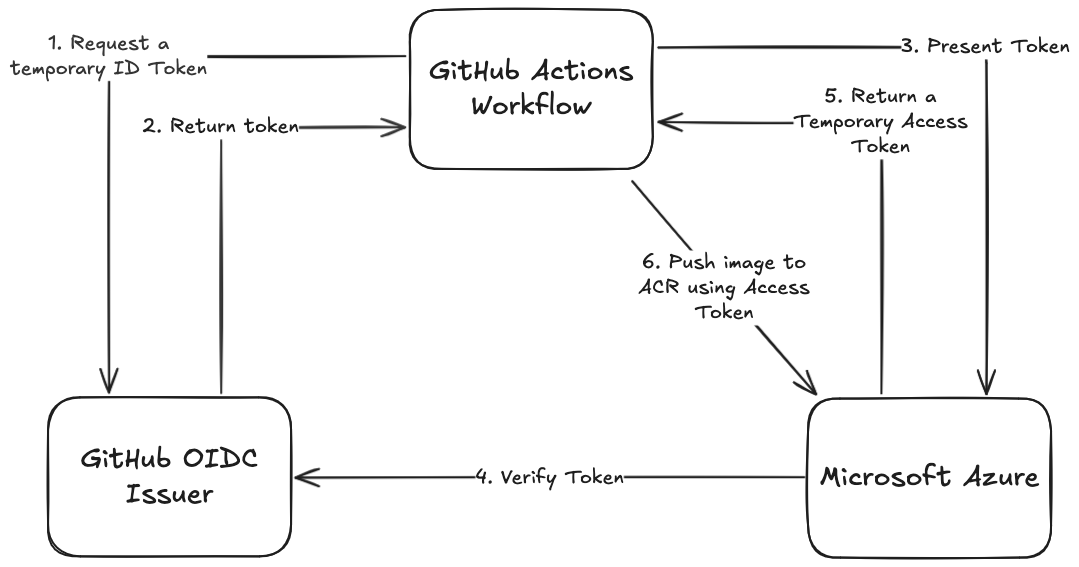

Let’s say we have a GitHub Actions workflow that builds a container image, and needs to push this image to Microsoft Azure Container Registry (ACR).

Here is a high-level diagram, with GitHub Actions as the workload, GitHub as the IDP and Microsoft Azure Container Registry (ACR) as the RP:

Important

You might be curious as to how the Actions Workflow is able to request an ID token from GitHub in the first place. Each Workload/IDP combination has a unique way of doing this, but in all cases, there is implicit trust between the workload and the IDP, which is managed and secured by the platform itself.

In the case of GitHub Actions, the workflow can request an ID token by using the $ACTIONS_ID_TOKEN_REQUEST_TOKEN environment variable, which is automatically provided by GitHub Actions.

In the case of Kubernetes, the workload uses its service account token (mounted into the pod at startup) to request an ID token from the Kubernetes API server.

In all cases, the workload has implicit access to the IDP.

Example GitHub OIDC Token #

To better understand what these ID tokens look like in practice, here’s an example of a decoded GitHub Actions OIDC token:

{

"typ": "JWT",

"alg": "RS256",

"x5t": "example-thumbprint",

"kid": "example-key-id"

}

{

"jti": "example-id",

"sub": "repo:octo-org/octo-repo:environment:prod",

"environment": "prod",

"aud": "https://github.com/octo-org",

"ref": "refs/heads/main",

"sha": "example-sha",

"repository": "octo-org/octo-repo",

"repository_owner": "octo-org",

"actor_id": "12",

"repository_visibility": "private",

"repository_id": "74",

"repository_owner_id": "65",

"run_id": "example-run-id",

"run_number": "10",

"run_attempt": "2",

"runner_environment": "github-hosted",

"actor": "octocat",

"workflow": "example-workflow",

"head_ref": "",

"base_ref": "",

"event_name": "workflow_dispatch",

"ref_type": "branch",

"job_workflow_ref": "octo-org/octo-automation/.github/workflows/oidc.yml@refs/heads/main",

"iss": "https://token.actions.githubusercontent.com",

"nbf": 1632492967,

"exp": 1632493867,

"iat": 1632493567

}

This token contains rich contextual information about the GitHub Actions run, which can be used by the RP for fine-grained authorization decisions.

Token Exchange & Verification - Under the Hood #

This all seems like magic, how does this actually work? If you’re curious about the details, keep reading! Otherwise, look out for my future posts where I’ll show you how to implement this in practice.

Token Exchange #

We should note that Relying Parties follow one of two methods for token exchange:

Standardized Token Exchange (RFC 8693): This is a standardized method for exchanging tokens between different systems. It allows the workload to exchange an ID token for an access token in a secure and standardized way using the spec defined in RFC 8693. You’ll most commonly see this used with Google Cloud Platform (GCP), which sticks to the standard. Here’s an example:

# Exchange the ID token for a temporary access token ACCESS_TOKEN=$(curl -X POST "https://sts.googleapis.com/v1/token" \ -H "Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded" \ -d "grant_type=urn:ietf:params:oauth:grant-type:token-exchange" \ -d "audience=//iam.googleapis.com/projects/PROJECT_NUMBER/locations/global/workloadIdentityPools/POOL_ID/providers/PROVIDER_ID" \ -d "scope=<https://www.googleapis.com/auth/cloud-platform>" \ -d "requested_token_type=urn:ietf:params:oauth:token-type:access_token" \ -d "subject_token=EXTERNAL_OIDC_TOKEN" \ -d "subject_token_type=urn:ietf:params:oauth:token-type:jwt" \ | jq -r '.access_token') # Now use the temporary access token to access GCP resources curl -H "Authorization: Bearer $ACCESS_TOKEN" \ "https://cloudresourcemanager.googleapis.com/v1/projects"Proprietary Token Exchange: Most RPs like Azure, AWS, etc, have their own proprietary methods for exchanging tokens. In some cases they’re similar to RFC 8693, but in others they are completely different.

For example with Cloudsmith (a SaaS artifact management platform), the token exchange is a lot simpler, and done via a proprietary endpoint that accepts the ID token in a JSON payload, along with the service account on the Cloudsmith side that the workload wants to assume the identity of:

# Exchange the ID token for a temporary access token ACCESS_TOKEN=$(curl -X POST https://api.cloudsmith.io/openid/$CLOUDSMITH_ORG/ \ -H "Content-Type: application/json" \ -d "{ "oidc_token": "$EXTERNAL_OIDC_TOKEN", "service_slug": "$SERVICE_ACCOUNT_SLUG" }" | jq -r '.token') # Now use the temporary access token to access Cloudsmith resources curl -H "X-Api-Key: $ACCESS_TOKEN" \ "https://api.cloudsmith.io/orgs/"

Token Verification #

While the token exchange process varies between RPs, the token verification process is generally consistent across all implementations. Following a number of RFCs, including RFC 7519 (JWT), RFC 7515 (JWS), RFC 7517 (JWK), and RFC 8414 (OIDC Discovery).

When the RP receives an ID token from the workload, it performs several verification steps to ensure the token’s authenticity and validity:

Parse the Token: The RP parses the ID token, which is typically in JWT format, to extract its header, payload, and signature.

Validate the Header: The RP checks the token’s header for the

alg(algorithm) andkid(key ID) fields. Thealgfield indicates the signing algorithm used, while thekidfield helps identify the correct public key for signature verification.Discover the IDP’s Public Keys: The RP retrieves the IDP’s public keys from a well-known URL, typically found in the IDP’s OIDC discovery document (e.g.,

https://<IDP>/.well-known/openid-configuration). The base URL of the OIDC issuer is configured during the initial trust setup between the IDP and RP by the human administrator.The OIDC discovery document contains a

jwks_urifield that points to the JSON Web Key Set (JWKS) document endpoint.Verify the Signature: Using the

kidfrom the token’s header, the RP selects the appropriate public key from the JWKS document. It then verifies the token’s signature using this public key and the specified algorithm. This ensures that the token was issued by the trusted IDP and has not been tampered with.Validate the Claims: The RP checks the token’s claims (found in the payload) to ensure they meet specific criteria, such as:

Issuer (

iss): The RP verifies that theissclaim matches the expected issuer URL of the IDP.Subject (

sub): The RP checks that thesubclaim is present and contains a valid identifier for the workload.Audience (

aud): The RP checks that theaudclaim includes its own identifier, ensuring the token was intended for it, and not another RP.Expiration (

exp): The RP ensures that the token has not expired by checking theexpclaim against the current time.Issued At (

iat): The RP may check theiatclaim to ensure the token was issued recently, helping to prevent replay and clock skew attacks.Not Before (

nbf): The RP verifies that the token is valid for use by checking thenbfclaim against the current time. Allows for issuing tokens that become valid at a future time.Custom Claims: Depending on the implementation, the RP may also validate additional custom claims specific to the IDP that issued the token.

For example GitHub includes several custom claims in their ID tokens, such as:

repository: The repository the workflow is running in.ref: The git ref that triggered the workflow (branch or tag).actor: The user or app that initiated the workflow.workflow: The name of the workflow.run_id: The unique identifier of the workflow run.

Extract Identity Information: If all verification steps pass, the RP extracts the necessary identity information from the token’s claims to determine the workload’s identity and permissions. This information is then used to authorize the workload’s access to resources. In most cases, the RP maps the workload’s identity to a specific service account or role within its own system, granting the appropriate permissions based on this mapping.

Issue Access Token: Finally, the RP issues a short-lived access token to the workload, with the permissions and scopes defined by the service account or role mapped to it by the administrator. This access token is typically valid for a limited time and can be used to access the RP’s APIs or services.

Security Considerations #

While WIF significantly improves security compared to long-lived secrets, there are important considerations to keep in mind:

Trust Relationship Configuration and Claim Validation: The initial trust setup between the IDP and RP is critical. Misconfigured trust relationships can allow unauthorized workloads to obtain access tokens. Always follow the principle of least privilege when configuring audience claims and subject mappings. Proper validation of

sub,aud, and custom claims is essential, especially with shared IDP infrastructures like GitHub’s default issuer URL (https://token.actions.githubusercontent.com). Without validating claims likesub,repository,ref, and/oractor, an attacker could potentially issue a token from their own GitHub account to access resources intended for a different organization.Token Replay Attacks: Although tokens are short-lived, they can still be intercepted and replayed within their validity window. Ensure your infrastructure uses encrypted transport (TLS) for all token exchanges.

Clock Skew: Token validation relies on timestamp claims (

exp,iat,nbf). Significant clock differences between systems can cause valid tokens to be rejected or expired tokens to be accepted. Maintain synchronized system clocks and configure appropriate clock skew tolerance.

Conclusion #

WIF represents a fundamental shift in how we approach service-to-service authentication. By eliminating long-lived secrets, organizations can achieve:

- Reduced Attack Surface: No static credentials to leak or compromise

- Simplified Operations: No more credential rotation schedules or secret management overhead

- Improved Security Posture: Identity-based authentication with automatic token expiration eliminates the risks of forgotten or unrotated credentials

The technical foundation we’ve covered here, from OIDC token exchange to signature verification, enables secure, scalable authentication patterns that are becoming the new standard across cloud platforms.

In my upcoming posts, I’ll share how I’ve implemented WIF across various platforms including GitHub Actions, Azure, and Kubernetes. These real-world examples will demonstrate practical approaches to eliminating long-lived secrets in modern infrastructure. Stay tuned for hands-on guides that show WIF in action!